On 15 November, the Zukunfskolleg organized a University Day in collaboration with the Hegau Bodensee Seminar entitled “Exploring Nature Around the World”.

Three ZUKOnnect Fellows from different disciplines offered workshops and interacted with pupils of the Hegau Bodensee Seminar (aged 16–18) to share their fascination for nature around the world.

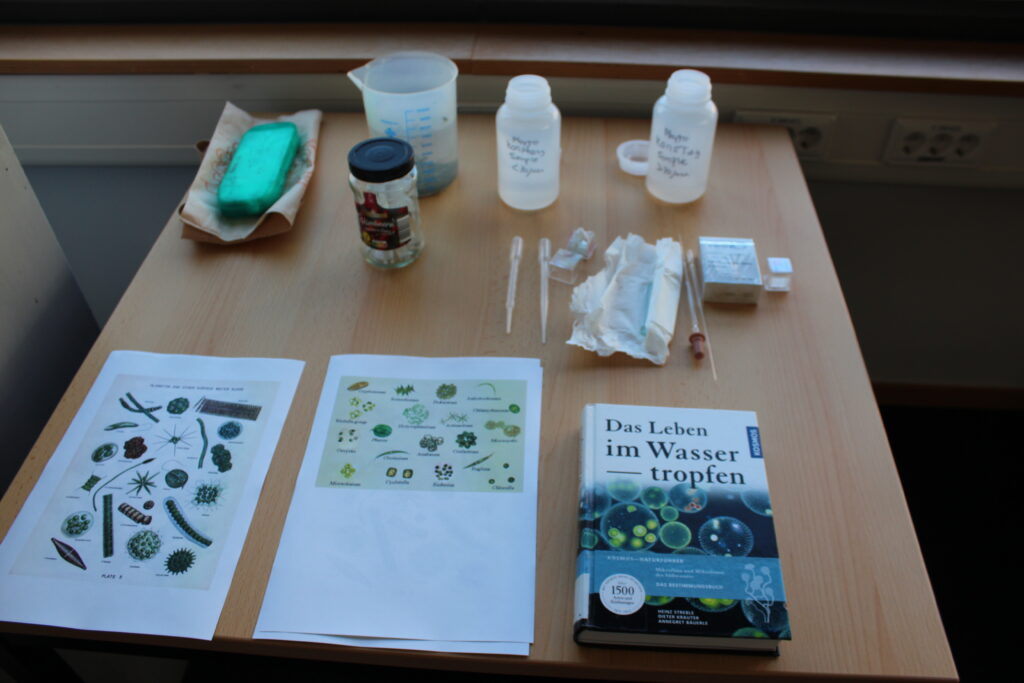

Maria Sol Porcel (from Argentina/ Department of Biology) provided a workshop about “Sweetwater Fish”.

At the beginning, the participants learned a lot about limnology: Limnology is a branch of ecology that studies freshwater systems, such as lakes, ponds, rivers, and reservoirs, as well as the interactions between aquatic organisms and their environment. Like oceanography, limnology is a highly integrative science where physics, chemistry and biology interact. The basaltic plateaus of the Patagonian Steppe (southern Argentina) are home to numerous lakes that differ in limnological characteristics and are the breeding habitat for endemic and critically endangered aquatic birds. In recent years, these lakes have experienced reduced water levels, shifting from a clear-vegetated to a turbid state. Exotic fish have also been introduced in naturally fishless lakes for sport fishing.

(PR & Science Communication Zukunftskolleg, University of Konstanz)

Maria Sol Porcel explained: “Our studies show that fish have impacted local environmental conditions and plankton communities, which are the most severe during dry periods. Ecosystem metabolism links environmental factors and food webs by regulating matter and energy flow through carbon production, consumption, and decomposition. As both reduced water levels and fish may shift metabolic processes, our goal is to quantify these processes (primary production and respiration) in shallow lakes in summer using high-frequency sensors. It is essential to understand the carbon cycle and the role of these ecosystems in the carbon cycle, and predict ecosystem response to climate change.”

The goal of her workshop was to provide an overview of limnological research, including sampling methods, and to explore the diversity of freshwater communities. She focused on the lakes of the Patagonian steppe, examining their unique ecological dynamics and discussing key conservation challenges.

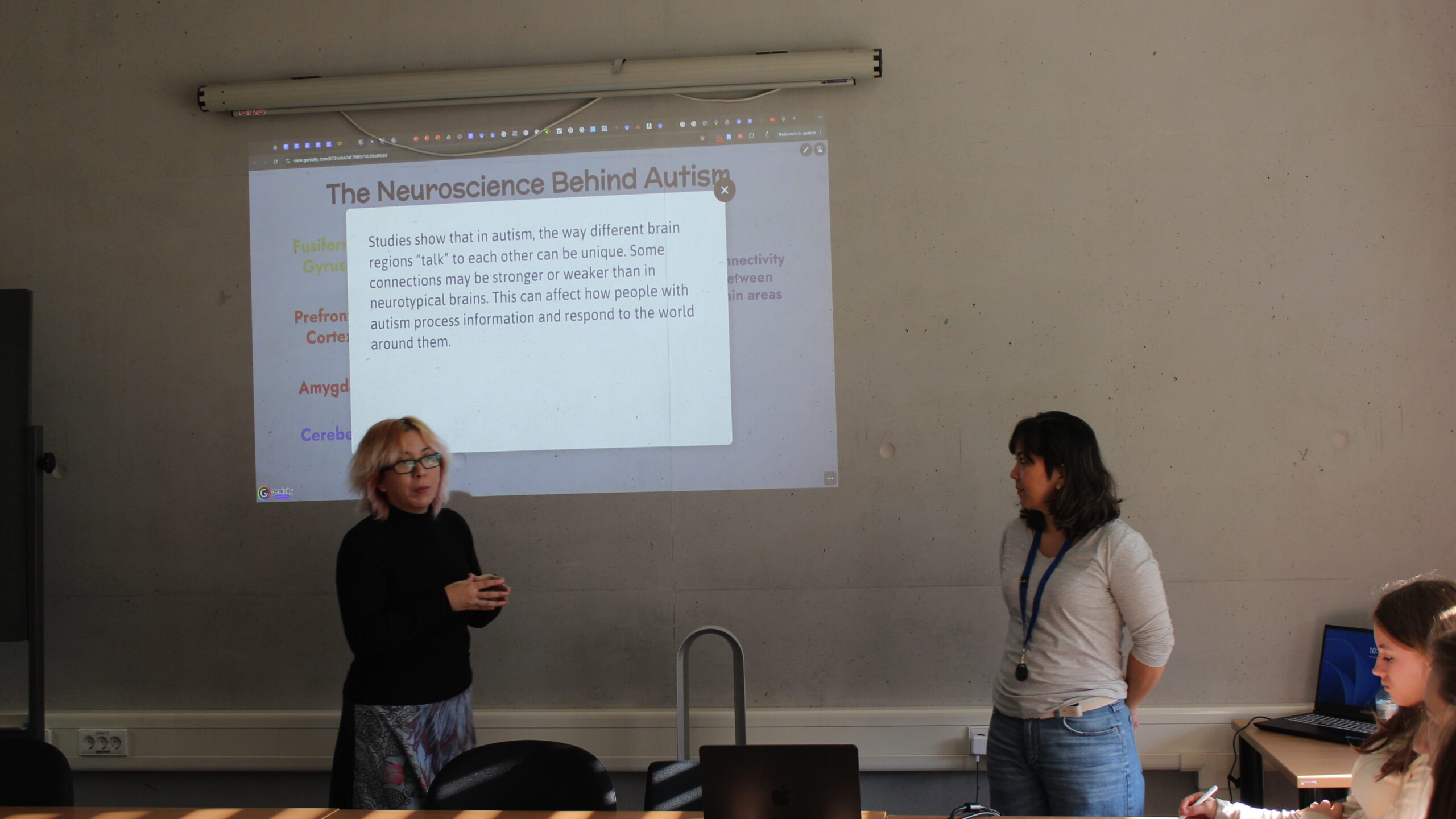

Autism from an interdisciplinary perspective

Cinthia Misaka (from Brazil/ Linguistics) and Antonieta Martinez (from Mexico/ Psychology and Computer and Information Science) offered a workshop entitled “Unlocking Autism: Step into the Neurodivergent Mind”.

(PR & Science Communication Zukunftskolleg, University of Konstanz)

They gave an introduction to the cognitive, neurological and linguistic traits of individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Students could explore key aspects of neurodivergence, gaining insights into how language and communication differ in people with ASD. Through interactive, hands-on activities, the participants experienced what it feels like to navigate social situations as a neurodivergent person; e.g. the students engaged in a communication task – such as retelling a short story or sharing a personal experience – while simultaneously being exposed to overlapping background noises or conversations that simulate auditory overload. This activity allowed them to experience first-hand the sensory challenges individuals with ASD may face in noisy environments and understand how excessive auditory stimuli can hinder effective communication.

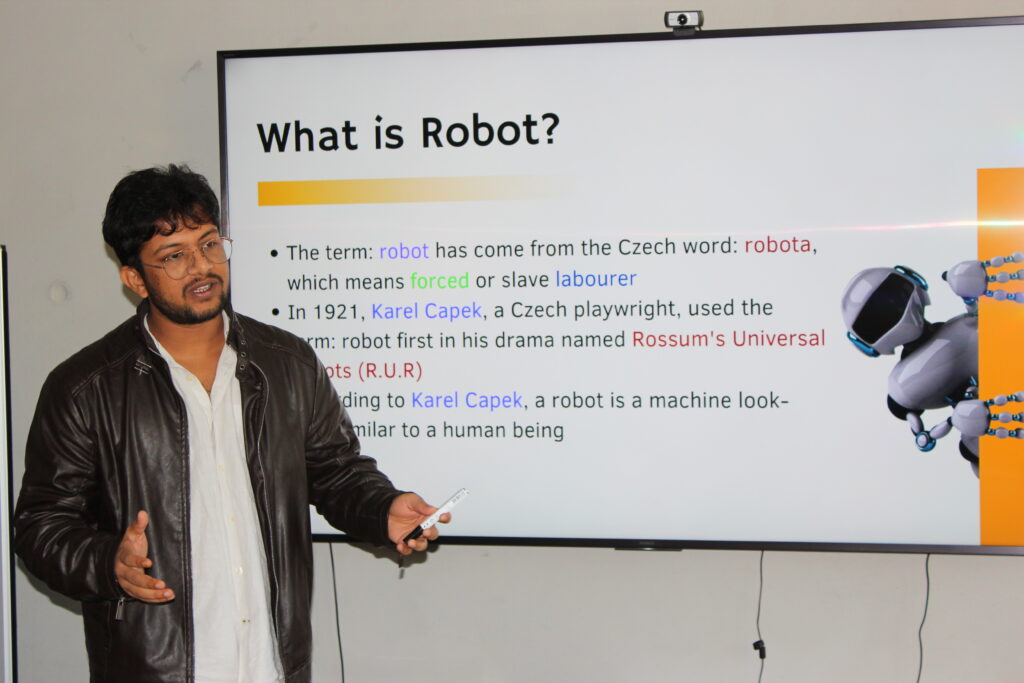

Robots in the swarm

Swadhin Agrawal (from India/ Informatics) discussed with the pupils “What is Swarm Robotics?”.

He made clear: “Robots are more than just machines. They can sense their surroundings, interpret and process the environment, and perform tasks. Robots are ubiquitous these days, especially ones such as self-driving cars, autonomous cleaning robots, drones, and many others. The basic principle that most of them work on is based on sense, plan, and act.”

(PR & Science Communication Zukunftskolleg, University of Konstanz)

In the workshop, the students gained more insights into these basic principles of what a robot is and how it works. Swadhin explained: “As the number of robots increases at a pace faster than ever at current times, we are reaching a point where each person will be surrounded by tens and hundreds of robots. In such a situation, the traditional approach of designing intelligent robots loaded with expensive equipment fails badly because we need to design algorithms considering all the worst-case possibilities, which is mostly impossible without making assumptions about robots’ task specialty. Natural collective systems like humans, ants, and fishes have made it through many natural disasters, and they work socially together flawlessly in the real world to achieve the desired objectives and survive. For instance, in the case of ants, each ant perhaps does not have much sense of its surroundings except for eating, lifting objects, and reproducing. Still, they collectively end up foraging in a group, building nests, and whatnot.”

The participants delved into how such behavioural principles from the social animal collectives like eating, following, etc. can be adapted to groups consisting of simple and not-too-expensive robots to let them achieve autonomy at the group level while not having to plan each of their missions.

Swarm Robotics

The Workshop on swarm robotics at the university of Constance within the program of the Hegau-Bodensee-Seminar was presented by Swadhin Agrawal, a PhD fellow from the Department of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering at IISER Bhopal. The seminar explored how robots function, the difference between multi robot systems and robot swarms and the defection in animal groups as well as robot swarms.

In the beginning the fellow introduced himself and talked about the things he’s working on for his PhD, the history of Ai and the future possibilities of using it. The prospects of Ai only became popular, because of the possible future usage in many different fields, like medicine and exploring space. To be able to understand the concept of swarm robotics we talked about the question “What is a robot?”. A robot thinks similar like a calculator, processing input, but with added capabilities to sense their environment through sensors and act through motors.

The presenter explained that robots work using a basic control loop with four steps: input, processing, action, and error correction. This loop helps robots sense their surroundings, make decisions, and act while reducing mistakes. Single robots can work on their own using this method. However, multi-robot systems face problems, like a single robot failing and disrupting the whole group. These systems can also behave unpredictably if one robot stops working. Swarm robotics offers a better solution because it is decentralised, meaning the group can keep functioning even if some robots fail.

Swarm robotics have many useful applications. They can for example, be used to create tiny medical robots that treat illnesses at a microscopic level. Swarm robots can also explore the ocean, helping to study large and hard-to-reach underwater areas.

By observing natural swarms like bees, ants, birds, and fish, scientists gain ideas for designing robotic systems that work together in similar ways.

After talking about this, we played a game as a group (picture 2), where we all took another persons hands and tried to entangle us. This showed us, that at least one person will take the commando in this situation and lead the group in their task. In robot swarms this is the case as well, which is why we talked about the important topic of the emergence of leadership and the dynamic of defection within swarms. The fellow Swadhin asked interesting questions, like how leadership can form in a swarm without a set leader and whether defecting agents—those who don’t follow the group—might actually help the swarm. Using models, the seminar showed that defectors can sometimes join cooperators or even help the swarm reach its goals faster.

The Couzin Model was used to explain these behaviours, focusing on how agents stay close to each other while avoiding collisions. The message of the study is, that if a swarm defects it reaches its goal more quickly.

The presenter talked about his four years of research in swarm robotics. He explained how he used tools like Python, Gazebo, and ROS.org to simulate and test swarm behaviour. He also emphasised how important lab experiments are for improving and proving these models.

In the end he showed us the so called swarmies in his laboratory, on which the fellow has been working for some time now. The swarmies are a type of simple robot, with which scientists explore swarm robotics, if you can arrange a swarm were they asses their own leader without knowing who it is and how leadership emerges in their behaviour.

The seminar ended with a summary of key points, highlighting how swarm robotics could transform fields like medicine and exploration. It stressed the need to understand how cooperation and defection work in swarm systems. Questions like how leadership develops and how defecting agents can help offer exciting ideas for future research. The session closed with a simulation that combined the theory and practice discussed, giving participants a better understanding of swarm robotics’ complexity and usefulness.

To conclude, the seminar was very educational and interesting and I am very glad about having been able to participate.